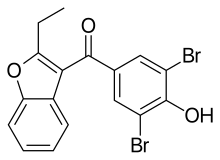

Benzbromarone

Benzbromarone là một tác nhân uricosuric và chất ức chế không cạnh tranh của xanthine oxyase [1] được sử dụng trong điều trị bệnh gút, đặc biệt là khi allopurinol, điều trị đầu tay, thất bại hoặc tạo ra tác dụng phụ không thể dung nạp. Nó có cấu trúc liên quan đến amiodarone chống loạn nhịp tim.[2]

| |

| Dữ liệu lâm sàng | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Tên thuốc quốc tế |

| Mã ATC | |

| Các định danh | |

Tên IUPAC

| |

| Số đăng ký CAS | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| Định danh thành phần duy nhất | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.020.573 |

| Dữ liệu hóa lý | |

| Công thức hóa học | C17H12Br2O3 |

| Khối lượng phân tử | 424.083 g/mol |

| Mẫu 3D (Jmol) | |

| Điểm nóng chảy | 161 đến 163 °C (322 đến 325 °F) |

SMILES

| |

Định danh hóa học quốc tế

| |

| (kiểm chứng) | |

Benzbromarone có hiệu quả cao và dung nạp tốt,[3][4][5][6] và các thử nghiệm lâm sàng vào đầu năm 1981 và gần đây vào tháng 4 năm 2008 đã cho thấy nó vượt trội hơn cả allopurinol, một chất ức chế oxy hóa xanthine không uricosuric, và probenecid, một loại thuốc uricosuric khác.[7][8]

Cơ chế hoạt động

sửaBenzbromarone là một chất ức chế CYP2C9 rất mạnh.[2][9] Một số chất tương tự của thuốc đã được phát triển dưới dạng chất ức chế CYP2C9 và CYP2C19 để sử dụng trong nghiên cứu.[10][11]

Lịch sử

sửaBenzbromarone được giới thiệu vào những năm 1970 và được xem là có ít phản ứng phụ nghiêm trọng liên quan. Nó đã được đăng ký tại khoảng 20 quốc gia trên khắp Châu Âu, Châu Á và Nam Mỹ.

Năm 2003, loại thuốc này đã bị Sanofi-Synthélabo thu hồi, sau khi có báo cáo về độc tính gan nghiêm trọng, mặc dù nó vẫn được các công ty dược phẩm khác bán trên thị trường ở một số nước.[12]

Tham khảo

sửa- ^ Sinclair, DS; Fox, IH (1975). “The pharmacology of hypouricemic effect of benzbromarone”. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2 (4): 437–45. PMID 1206675.

- ^ a b Kumar, V.; Locuson, CW; Sham, YY; Tracy, TS (2006). “Amiodarone Analog-Dependent Effects on CYP2C9-Mediated Metabolism and Kinetic Profiles”. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 34 (10): 1688–96. doi:10.1124/dmd.106.010678. PMID 16815961.

- ^ Heel, R.C.; Brogden, R.N.; Speight, T.M.; Avery, G.S. (1977). “Benzbromarone”. Drugs. 14 (5): 349–66. doi:10.2165/00003495-197714050-00002. PMID 338280.

- ^ Masbernard, A; Giudicelli, CP (1981). “Ten years' experience with benzbromarone in the management of gout and hyperuricaemia” (PDF). South African Medical Journal. 59 (20): 701–6. PMID 7221794.

- ^ Perez-Ruiz, F; Alonso-Ruiz, A; Calabozo, M; Herrero-Beites, A; Garcia-Erauskin, G; Ruiz-Lucea, E (1998). “Efficacy of allopurinol and benzbromarone for the control of hyperuricaemia. A pathogenic approach to the treatment of primary chronic gout”. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 57 (9): 545–9. doi:10.1136/ard.57.9.545. PMC 1752740. PMID 9849314.

- ^ Reinders, Mattheus K.; Roon, Eric N.; Houtman, Pieternella M.; Brouwers, Jacobus R. B. J.; Jansen, Tim L. Th. A. (2007). “Biochemical effectiveness of allopurinol and allopurinol-probenecid in previously benzbromarone-treated gout patients”. Clinical Rheumatology. 26 (9): 1459–65. doi:10.1007/s10067-006-0528-3. PMID 17308859.

- ^ Schepers, GW (1981). “Benzbromarone therapy in hyperuricaemia; comparison with allopurinol and probenecid”. The Journal of International Medical Research. 9 (6): 511–5. doi:10.1177/030006058100900615. PMID 7033016.

- ^ Reinders, M K; Van Roon, E N; Jansen, T L T. A; Delsing, J; Griep, E N; Hoekstra, M; Van De Laar, M A F J; Brouwers, J R B J (2008). “Efficacy and tolerability of urate-lowering drugs in gout: A randomised controlled trial of benzbromarone versus probenecid after failure of allopurinol”. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 68 (1): 51–6. doi:10.1136/ard.2007.083071. PMID 18250112.

- ^ Hummel, M. A. (2005). “CYP2C9 Genotype-Dependent Effects on in Vitro Drug-Drug Interactions: Switching of Benzbromarone Effect from Inhibition to Activation in the CYP2C9.3 Variant”. Molecular Pharmacology. 68 (3): 644–51. doi:10.1124/mol.105.013763. PMC 1552103. PMID 15955872.

- ^ Locuson, Charles W.; Rock, Denise A.; Jones, Jeffrey P. (2004). “Quantitative Binding Models for CYP2C9 Based on Benzbromarone Analogues†”. Biochemistry. 43 (22): 6948–58. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.127.2015. doi:10.1021/bi049651o. PMID 15170332.

- ^ Locuson, Charles W.; Suzuki, Hisashi; Rettie, Allan E.; Jones, Jeffrey P. (2004). “Charge and Substituent Effects on Affinity and Metabolism of Benzbromarone-Based CYP2C19 Inhibitors”. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 47 (27): 6768–76. doi:10.1021/jm049605m. PMID 15615526.

- ^ Lee, Ming-Han H; Graham, Garry G; Williams, Kenneth M; Day, Richard O (2008). “A Benefit-Risk Assessment of Benzbromarone in the Treatment of Gout”. Drug Safety. 31 (8): 643–65. doi:10.2165/00002018-200831080-00002. PMID 18636784.