Thành viên:Ctdbsclvn/nháp 1

Sứ mệnh Apollo 7 đã thực hiện lần truyền hình trực tiếp đầu tiên trên tàu của một phi thuyền có người lái của Mỹ | |

| Dạng nhiệm vụ | Chuyến bay có người lái lên quỹ đạo Trái Đất sử dụng CSM (C) |

|---|---|

| Nhà đầu tư | NASA[1] |

| COSPAR ID | 1968-089A (phi thuyền), 1968-089B (S-IVB)[2] |

| SATCAT no. | 3486[3] |

| Thời gian nhiệm vụ | 10 ngày, 20 giờ, 9 phút, 3 giây |

| Quỹ đạo đã hoàn thành | 163[4] |

| Các thuộc tính thiết bị vũ trụ | |

| Thiết bị vũ trụ | Apollo CSM-101 |

| Nhà sản xuất | North American Rockwell |

| Khối lượng phóng | 36.419 pound (16.519 kg)[5] |

| Khối lượng hạ cánh | 11.409 pound (5.175 kg)[6] |

| Phi hành đoàn | |

| Số lượng phi hành đoàn | 3 |

| Thành viên | |

| Dấu hiệu cuộc gọi | Apollo 7 |

| Bắt đầu nhiệm vụ | |

| Ngày phóng | 11 tháng 10 năm 1968, 15:02:45 UTC |

| Tên lửa | Saturn IB SA-205 |

| Địa điểm phóng | Mũi Kennedy, LC-34 |

| Kết thúc nhiệm vụ | |

| Phục hồi bởi | USS Essex |

| Ngày hạ cánh | 22 tháng 10 năm 1968, 11:11:48 UTC |

| Nơi hạ cánh | Bắc Đại Tây Dương 27°32′B 64°04′T / 27,533°B 64,067°T[7] |

| Các tham số quỹ đạo | |

| Hệ quy chiếu | Địa tâm |

| Chế độ | Quỹ đạo Trái Đất tầm thấp |

| Cận điểm | 227 kilômét (123 nmi)[2] |

| Viễn điểm | 301 kilômét (163 nmi)[2] |

| Độ nghiêng | 31,6 độ[2] |

| Chu kỳ | 89,55 phút[2] |

| Kỷ nguyên | 13 tháng 10 năm 1968[8] |

Từ trái sang phải: Eisele, Schirra, Cunningham | |

Apollo 7 (11–22 tháng 10 năm 1968) là chuyến bay có người lái đầu tiên thuộc chương trình không gian Apollo của NASA. Sứ mệnh cũng chứng kiến cơ quan này tiếp tục các chuyến bay đưa con người vào vũ trụ kể từ sau vụ hỏa hoạn khiến ba phi hành gia Apollo 1 thiệt mạng trong cuộc thử nghiệm phóng diễn tập vào ngày 27 tháng 1 năm 1967. Chỉ huy phi hành đoàn Apollo 7 là Walter M. Schirra, với Donn F. Eisele làm phi công mô-đun chỉ huy và R. Walter Cunningham đảm nhiệm chức vụ phi công mô-đun Mặt Trăng (ông đã được chỉ định như vậy mặc dù Apollo 7 không mang theo Mô-đun Mặt Trăng).

Ba phi hành gia này ban đầu được chỉ định tham gia chuyến bay Apollo có người lái thứ hai và sau đó làm phi hành đoàn dự bị cho Apollo 1. Sau vụ hỏa hoạn Apollo 1, các chuyến bay có phi hành đoàn đã bị đình chỉ trong thời gian điều tra nguyên nhân tai nạn và thực hiện những cải tiến đối với tàu vũ trụ, các quy trình an toàn cũng như thực hiện các chuyến bay thử nghiệm không người lái. Quyết tâm ngăn chặn đám cháy tái diễn, phi hành đoàn đã dành thời gian dài để theo dõi việc xây dựng các mô-đun chỉ huy và dịch vụ Apollo (CSM) của họ. Quá trình đào tạo tiếp tục diễn ra trong phần lớn 21 tháng tạm dừng sau thảm họa Apollo 1.

Apollo 7 phóng ngày 11 tháng 10 năm 1968 từ Trạm không quân Mũi Kennedy ở Florida và rơi xuống Đại Tây Dương sau mười một ngày. Việc thử nghiệm bao quát đối với CSM đã diễn ra và cũng là buổi phát sóng truyền hình trực tiếp đầu tiên từ tàu vũ trụ của Mỹ. Bất chấp căng thẳng giữa phi hành đoàn và những người điều khiển mặt đất, sứ mệnh này hoàn toàn thành công về mặt kỹ thuật, giúp NASA tự tin đưa Apollo 8 vào quỹ đạo quanh Mặt Trăng hai tháng sau đó. Một phần vì những căng thẳng này, không ai trong số phi hành đoàn bay vào vũ trụ nữa, mặc dù Schirra thông báo rằng ông sẽ nghỉ việc tại NASA sau chuyến bay. Apollo 7 đã hoàn thành sứ mệnh thử nghiệm CSM của Apollo 1 trên quỹ đạo Trái Đất tầm thấp và đánh dấu một bước tiến quan trọng hướng tới mục tiêu đưa phi hành gia hạ cánh xuống Mặt Trăng của NASA.

Bối cảnh và nhân sự

sửa| Vai trò | Phi hành gia[9] | |

|---|---|---|

| Chỉ huy | Walter M. Schirra Chuyến bay thứ ba và cuối cùng | |

| Phi công Mô-đun Chỉ huy | Donn F. Eisele Chuyến bay duy nhất | |

| Phi công Mô-đun Mặt Trăng[a] | R. Walter Cunningham Chuyến bay duy nhất | |

Schirra, một trong những phi hành gia của nhóm "Mercury Seven" ban đầu, tốt nghiệp Học viện Hải quân Hoa Kỳ vào năm 1945. Ông bay trên Mercury-Atlas 8 vào năm 1962, chuyến bay thứ năm có phi hành đoàn của Dự án Mercury và là chuyến bay thứ ba vào quỹ đạo, sau đó ông làm phi công chỉ huy cho Gemini 6A vào năm 1965. Ông là thuyền trưởng 45 tuổi của Hải quân vào thời điểm Apollo 7. Eisele tốt nghiệp Học viện Hải quân năm 1952 với bằng B.S. trong lĩnh vực hàng không. Ông được bầu vào Lực lượng Không quân và là thiếu tá 38 tuổi vào thời điểm Apollo 7.[10] Cunningham gia nhập Hải quân Hoa Kỳ năm 1951, bắt đầu huấn luyện bay vào năm sau và phục vụ trong phi đội bay Thủy quân lục chiến từ năm 1953 đến năm 1956, và là một thường dân, 36 tuổi, phục vụ trong lực lượng dự bị của Thủy quân lục chiến với cấp bậc thiếu tá, vào thời điểm Apollo 7.[10][11] Ông nhận bằng vật lý của UCLA, bằng B.A. vào năm 1960 và lấy bằng Thạc sĩ vào năm 1961. Cả Eisele và Cunningham đều được chọn vào nhóm phi hành gia thứ ba của NASA vào năm 1963.[10]

Eisele ban đầu được xếp vào một vị trí trong phi hành đoàn Apollo 1 của Gus Grissom cùng với Ed White, nhưng vài ngày trước khi có thông báo chính thức vào ngày 25 tháng 3 năm 1966, Eisele đã dính chấn thương vai và cần phải phẫu thuật. Thay vào đó, Roger Chaffee được giao vị trí này và Eisele được bổ nhiệm lại vào phi hành đoàn của Schirra.[12]

Schirra, Eisele và Cunningham lần đầu tiên được chỉ định vào phi hành đoàn Apollo vào ngày 29 tháng 9 năm 1966. Họ dự định sẽ bay chuyến bay thử nghiệm thứ hai trên quỹ đạo Trái Đất của Mô-đun Chỉ huy Apollo (CM).[13] Mặc dù rất vui mừng khi còn là một tân binh khi được bổ nhiệm vào phi hành đoàn chính mà không phải phục vụ ở phi hành đoàn dự phòng, Cunningham vẫn lo lắng vì chuyến bay thử nghiệm thứ hai trên quỹ đạo Trái Đất, được đặt tên là Apollo 2, dường như không cần thiết nếu như Apollo 1 thành công. Sau đó ông được biết rằng Giám đốc Điều hành Phi hành đoàn Deke Slayton, một phi hành gia khác trong nhóm Mercury Seven, người đã phải ngừng bay vì lý do y tế và chuyển sang giám sát các phi hành gia, đã lên kế hoạch, với sự hỗ trợ của Schirra, sẽ chỉ huy sứ mệnh nếu ông có được giấy phép y tế. Khi điều này không xảy ra, Schirra vẫn nắm quyền chỉ huy phi hành đoàn và vào tháng 11 năm 1966, Apollo 2 bị hủy bỏ và phi hành đoàn của Schirra được chỉ định làm dự phòng cho đội bay của Grissom.[14] Thomas P. Stafford – người tại thời điểm đó được chỉ định làm chỉ huy dự phòng của cuộc thử nghiệm trên quỹ đạo thứ hai – tuyên bố rằng việc hủy bỏ nhiệm vụ diễn ra sau khi Schirra và phi hành đoàn của ông gửi danh sách các yêu cầu lên ban quản lý NASA (Schirra muốn sứ mệnh bao gồm một mô-đun Mặt Trăng và một CM có khả năng ghép nối với nó), và việc chỉ định làmdự phòng khiến Schirra phàn nàn rằng Slayton và Chánh Văn phòng Phi hành gia Alan Shepard đã hủy hoại sự nghiệp của ông.[15]

Ngày 27 tháng 1 năm 1967, phi hành đoàn của Grissom đang tiến hành thử nghiệm bệ phóng cho sứ mệnh dự kiến vào ngày 21 tháng 2 thì một đám cháy bùng phát trong cabin khiến cả ba người thiệt mạng.[16] Theo sau là một cuộc đánh giá toàn diện về tính an toàn của chương trình Apollo.[17] Ngay sau vụ cháy, Slayton yêu cầu Schirra, Eisele và Cunningham thực hiện nhiệm vụ đầu tiên sau thời gian tạm dừng.[18] Apollo 7 sẽ sử dụng tàu vũ trụ Block II được thiết kế cho các sứ mệnh Mặt Trăng, trái ngược với CSM Block I được sử dụng cho Apollo 1, vốn chỉ nhằm mục đích sử dụng cho các sứ mệnh quay quanh quỹ đạo Trái Đất ban đầu, do nó thiếu khả năng ghép nối với mô-đun Mặt Trăng. CM và bộ đồ vũ trụ của các phi hành gia đã được thiết kế lại một cách bao quát để giảm nguy cơ lặp lại vụ tai nạn đã cướp đi sinh mạng của phi hành đoàn đầu tiên.[19] Phi hành đoàn của Schirra sẽ thử nghiệm các hệ thống hỗ trợ sự sống, động cơ đẩy, hướng dẫn và điều khiển trong nhiệm vụ "kết thúc mở" này (có nghĩa là nó sẽ được mở rộng mỗi khi vượt qua một bài kiểm tra). Thời lượng được giới hạn là 11 ngày, giảm so với giới hạn 14 ngày ban đầu của Apollo 1.[20]

Phi hành đoàn dự phòng bao gồm Stafford là chỉ huy, John W. Young là phi công mô-đun chỉ huy và Eugene A. Cernan là phi công mô-đun Mặt Trăng. Về sau họ đã trở thành phi hành đoàn chính của Apollo 10.[21] Ronald E. Evans, John L. 'Jack' Swigert và Edward G. Givens được chỉ định làm phi hành đoàn hỗ trợ cho sứ mệnh.[22] Givens qua đời trong một vụ tai nạn xe hơi vào ngày 6 tháng 6 năm 1967 nên William R. Pogue được chỉ định làm người thay thế ông. Evans đã tham gia thử nghiệm phần cứng tại Trung tâm Vũ trụ Kennedy (KSC). Swigert là liên lạc viên khoang vũ trụ (capsule communicator, viết tắt là CAPCOM) cho phi vụ phóng và đã nghiên cứu các khía cạnh điều hành của sứ mệnh. Pogue thì dành thời gian sửa đổi những thủ tục. Đội hỗ trợ cũng lấp đầy khi đội chính và đội dự phòng không thể có mặt.[23]

CAPCOM, nhân sự thuộc Kiểm soát Sứ mệnh chịu trách nhiệm liên lạc với tàu vũ trụ (khi ấy luôn là một phi hành gia) gồm Evans, Pogue, Stafford, Swigert, Young và Cernan. Các giám đốc chuyến bay là Glynn Lunney, Gene Kranz và Gerry Griffin.[24]

Chuẩn bị

sửaTheo Cunningham, Schirra ban đầu không mấy quan tâm đến việc thực hiện chuyến bay vũ trụ thứ ba nên đã bắt đầu tập trung vào sự nghiệp hậu NASA của mình. Tuy nhiên, việc thực hiện sứ mệnh đầu tiên sau vụ hỏa hoạn đã thay đổi mọi thứ: "Người ta miêu tả Wally là người được chọn để giải cứu chương trình không gian có người lái. Và đó là một nhiệm vụ đáng để Wally quan tâm".[25] Eisele lưu ý, "ngay sau vụ cháy, chúng tôi biết rằng số phận và tương lai của toàn bộ chương trình không gian có người lái – chưa kể đến làn da của chính chúng tôi – đang phụ thuộc vào việc Apollo 7 sẽ thành công hay thất bại".[26]

Do hoàn cảnh của vụ cháy, ban đầu phi hành đoàn không mấy tin tưởng vào nhân viên tại nhà máy của North American Aviation ở Downey, California, những người đã chế tạo các mô-đun chỉ huy Apollo, và họ đã quyết tâm theo dõi phi thuyền từng bước thông qua quá trình xây dựng và thử nghiệm. Điều này đã cản trở việc đào tạo, nhưng các trình mô phỏng của CM vẫn chưa sẵn sàng và họ biết rằng sẽ còn rất lâu nữa mới đến ngày phóng. Họ đã dành ra nhiều quãng thời gian dài ở Downey. Các thiết bị mô phỏng đã được xây dựng tại Trung tâm Tàu vũ trụ có Người lái ở Houston và tại KSC ở Florida. Khi những thứ này sẵn sàng để sử dụng, phi hành đoàn gặp khó khăn trong việc tìm đủ thời gian để làm mọi việc, ngay cả khi có sự trợ giúp của các đội dự phòng và hỗ trợ; phi hành đoàn thường làm việc 12 hoặc 14 giờ mỗi ngày. Sau khi CM được hoàn thành và chuyển đến KSC, trọng tâm đào tạo của phi hành đoàn chuyển sang Florida, mặc dù họ đã đến Houston để lập kế hoạch và họp kỹ thuật. Thay vì trở về nhà ở Houston vào cuối tuần, họ thường phải ở lại KSC để tham gia huấn luyện hoặc thử nghiệm tàu vũ trụ.[27] Theo cựu phi hành gia Tom Jones trong một bài báo năm 2018, Schirra, "với bằng chứng không thể chối cãi về những rủi ro mà phi hành đoàn của anh ta sẽ gặp phải, giờ đây đã có đòn bẩy to lớn với ban quản lý tại NASA và North American, và anh ta đã sử dụng nó. Trong phòng họp hoặc trên dây chuyền lắp ráp tàu vũ trụ, Schirra đã làm theo cách của mình".[28]

Phi hành đoàn Apollo 7 đã dành năm giờ huấn luyện cho mỗi giờ ở lại trên tàu mà họ có thể liệu trước nếu sứ mệnh kéo dài đủ 11 ngày. Ngoài ra, họ còn tham dự các cuộc họp giao ban kỹ thuật và các cuộc họp của phi công và tự mình nghiên cứu. Họ đã tiến hành huấn luyện sơ tán trên bệ phóng, huấn luyện thoát hiểm dưới nước để thoát khỏi phương tiện sau khi rơi xuống biển và học cách sử dụng thiết bị chữa cháy. Họ dã huấn luyện trên Máy tính Hướng dẫn Apollo (Apollo Guidance Computer) tại MIT. Mỗi thành viên phi hành đoàn đã dành 160 giờ trong các buổi mô phỏng CM, một số trong đó Kiểm soát Sứ mệnh ở Houston đã trực tiếp tham gia.[29] Thử nghiệm "plugs out" (tạm dịch là "rút phích cắm") – cuộc thử nghiệm đã giết chết phi hành đoàn Apollo 1 – được tiến hành với phi hành đoàn chính trên tàu vũ trụ nhưng với cửa sập vẫn mở.[30] Một lý do khiến phi hành đoàn Apollo 1 thiệt mạng là vì không thể mở được cửa sập mở vào trong trước khi ngọn lửa lan khắp cabin; điều này đã được thay đổi đối với Apollo 7.[31]

Các mô-đun chỉ huy tương tự như mô-đun được sử dụng trên Apollo 7 đã được thử nghiệm trong quá trình chuẩn bị thực hiện sứ mệnh. Phi hành đoàn gồm ba người (Joseph P. Kerwin, Vance D. Brand và Joe H. Engle) đã ở bên trong một CM được đặt trong buồng chân không tại Trung tâm Chuyến bay không gian có Người lái ở Houston trong 8 ngày vào tháng 6 năm 1968 để thử nghiệm các hệ thống tàu vũ trụ. Một phi hành đoàn khác (James Lovell, Stuart Roosa và Charles M. Duke) đã dành 48 giờ trên biển trên một chiếc CM được hạ xuống vịnh México từ một tàu hải quân vào tháng 4 năm 1968, để kiểm tra xem các hệ thống sẽ phản ứng như thế nào với nước biển. Các cuộc thử nghiệm sâu hơn được tiến hành vào tháng sau trên một chiếc xe tăng ở Houston. Các đám cháy được đốt trên một boilerplate[b] CM bằng cách sử dụng các thành phần và áp suất khí quyển khác nhau. Kết quả dẫn đến quyết định sử dụng 60% oxy và 40% nitơ trong CM khi phóng, và sẽ được thay thế bằng oxy tinh khiết áp suất thấp hơn trong vòng 4 giờ để cung cấp khả năng chống cháy đầy đủ. Các boilerplate tàu vũ trụ khác đã được thả xuống để thử nghiệm dù và để mô phỏng thiệt hại có thể xảy ra nếu CM rơi xuống đất liền. Tất cả các kết quả đều hài lòng.[33]

Trong quá trình chuẩn bị thực hiện sứ mệnh, Liên Xô đã gửi các tàu thăm dò không người lái Zond 4 và Zond 5 (Zond 5 mang theo hai con rùa cạn[34]) bay vòng quanh Mặt Trăng, dường như báo trước một sứ mệnh có phi hành đoàn đi vòng quanh Mặt Trăng. Mô-đun Mặt Trăng (LM) của NASA đang bị chậm trễ và Giám đốc Tàu vũ trụ của Chương trình Apollo, George Low, đã đề xuất rằng nếu Apollo 7 thành công thì Apollo 8 sẽ đi vào quỹ đạo Mặt Trăng mà không cần LM. Việc chấp nhận đề xuất của Low đã nâng cao ngân sách dành cho Apollo 7.[28] Theo Stafford, Schirra "rõ ràng cảm nhận được toàn bộ sức nặng của chương trình nhằm thực hiện một sứ mệnh thành công và kết quả là trở nên hay chỉ trích công khai hơn và hay chế nhạo hơn".[35]

Trong suốt các chương trình Mercury và Gemini, kỹ sư của McDonnell Aircraft là Guenter Wendt đã lãnh đạo các đội bệ phóng tàu vũ trụ, chịu trách nhiệm cuối cùng về tình trạng của tàu vũ trụ khi phóng. Ông đã nhận được sự tôn trọng và ngưỡng mộ của các phi hành gia, bao gồm cả Schirra.[36] Tuy nhiên, nhà thầu tàu vũ trụ đã thay đổi từ McDonnell (Mercury và Gemini) sang North American (Apollo), vì vậy Wendt không được làm chỉ huy bệ phóng cho Apollo 1.[37] Schirra kiên quyết muốn có Wendt trở lại làm trưởng nhóm cho chuyến bay Apollo của mình, đến nỗi ông đã nhờ sếp Slayton thuyết phục ban quản lý McDonnell thuê Wendt khỏi McDonnell, và đích thân Schirra đã vận động người quản lý hoạt động phóng của North American thay đổi ca làm việc của Wendt từ nửa đêm sang ban ngày để ông có thể trở thành chỉ huy bệ phóng cho Apollo 7. Wendt vẫn là chỉ huy bệ phóng cho toàn bộ chương trình Apollo.[37] Khi ông rời khu vực tàu vũ trụ khi bệ phóng được sơ tán trước khi phóng, sau khi Cunningham nói, "Tôi nghĩ Guenter đang đi", Eisele trả lời "Đúng, tôi nghĩ Guenter đã đi".[c][38][39][40][41]

Phần cứng

sửaTàu vũ trụ

sửaTàu vũ trụ Apollo 7 bao gồm Mô-đun Chỉ huy và Dịch vụ 101 (CSM-101), CSM Block II đầu tiên được bay. Tàu Block II có khả năng ghép nối với LM,[42] mặc dù không có chiếc nào bay trên Apollo 7. Tàu vũ trụ cũng bao gồm hệ thống thoát hiểm khi phóng (launch escape system) và adapter tàu vũ trụ - mô-đun Mặt Trăng (spacecraft-lunar module adapter, viết tắt là SLA, được đánh số là SLA-5), mặc dù cái sau không bao gồm LM và thay vào đó cung cấp cấu trúc lắp ghép giữa SM và Instrument Unit của S-IVB,[43][44] với chất làm cứng kết cấu (structural stiffener) được thay thế cho LM.[45] Hệ thống thoát hiểm khi phóng đã bị loại bỏ sau khi đánh lửa S-IVB,[46] trong khi SLA bị bỏ lại trên S-IVB đã sử dụng khi CSM tách khỏi nó trên quỹ đạo.[45]

Sau vụ cháy tàu Apollo 1, CSM Block II đã được thiết kế lại toàn diện – hơn 1.800 thay đổi đã được đề xuất, trong đó 1.300 đã được triển khai cho Apollo 7.[38] Nổi bật trong số này là cửa sập mở ra bên ngoài bằng nhôm và sợi thủy tinh mới, mà phi hành đoàn có thể mở trong bảy giây từ bên trong và đội ngũ bệ phóng trong mười giây từ bên ngoài. Những thay đổi khác bao gồm thay thế ống nhôm trong hệ thống oxy cao áp bằng thép không gỉ, thay thế vật liệu dễ cháy bằng vật liệu không cháy (bao gồm cả việc thay công tắc nhựa bằng công tắc kim loại) và, để bảo vệ phi hành đoàn trong trường hợp hỏa hoạn, một hệ thống oxy khẩn cấp để bảo vệ họ khỏi khói độc, cũng như thiết bị chữa cháy.[47]

Sau khi tàu Gemini 3 được Grissom mệnh danh là Molly Brown, NASA đã cấm đặt tên cho tàu vũ trụ.[48] Bất chấp lệnh cấm này, Schirra muốn đặt tên con tàu của mình là "Phoenix", nhưng NASA đã từ chối cho phép.[42] CM đầu tiên được cấp một tín hiệu gọi không phải tên sứ mệnh sẽ là của Apollo 9, mang một LM sẽ tách khỏi nó và sau đó ghép nối lại, nên cần có các tín gọi riêng biệt cho hai phương tiện.[49]

Phương tiện phóng

sửaSince it flew in low Earth orbit and did not include a LM, Apollo 7 was launched with the Saturn IB booster rather than the much larger and more powerful Saturn V.[50] That Saturn IB was designated SA-205,[42] and was the fifth Saturn IB to be flown—the earlier ones did not carry crews into space. It differed from its predecessors in that stronger propellant lines to the augmented spark igniter in the J-2 engines had been installed, so as to prevent a repetition of the early shutdown that had occurred on the uncrewed Apollo 6 flight; postflight analysis had shown that the propellant lines to the J-2 engines, also used in the Saturn V tested on Apollo 6, had leaked.[51]

The Saturn IB was a two-stage rocket, with the second stage an S-IVB similar to the third stage of the Saturn V,[52] the rocket used by all later Apollo missions.[50] The Saturn IB was used after the close of the Apollo Program to bring crews in Apollo CSMs to Skylab, and for the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project.[53]

Apollo 7 was the only crewed Apollo mission to launch from Cape Kennedy Air Force Station's Launch Complex 34. All subsequent Apollo and Skylab spacecraft flights (including Apollo–Soyuz) were launched from Launch Complex 39 at the nearby Kennedy Space Center.[50] Launch Complex 34 was declared redundant and decommissioned in 1969, making Apollo 7 the last human spaceflight mission to launch from the Cape Air Force Station in the 20th century.[50]

Điểm nhấn sứ mệnh

sửaThe main purposes of the Apollo 7 flight were to show that the Block II CM would be habitable and reliable over the length of time required for a lunar mission, to show that the service propulsion system (SPS, the spacecraft's main engine) and the CM's guidance systems could perform a rendezvous in orbit, and later make a precision reentry and splashdown.[28] In addition, there were a number of specific objectives, including evaluating the communications systems and the accuracy of onboard systems such as the propellant tank gauges. Many of the activities aimed at gathering these data were scheduled for early in the mission, so that if the mission was terminated prematurely, they would already have been completed, allowing for fixes to be made prior to the next Apollo flight.[54]

Phi vụ phóng và thử nghiệm

sửaApollo 7, the first crewed American space flight in 22 months, launched from Launch Complex 34 at 11:02:45 am EDT (15:02:45 UTC) on Friday, October 11, 1968.[38][55]

During the countdown, the wind was blowing in from the east. Launching under these weather conditions was in violation of safety rules, since in the event of a launch vehicle malfunction and abort, the CM might be blown back over land instead of making the usual water landing. Apollo 7 was equipped with the old Apollo 1-style crew couches, which provided less protection than later ones. Schirra later related that he felt the launch should have been scrubbed, but managers waived the rule and he yielded under pressure.[28]

Liftoff proceeded flawlessly; the Saturn IB performed well on its first crewed launch and there were no significant anomalies during the boost phase. The astronauts described it as very smooth.[38][56] The ascent made the 45-year-old Schirra the oldest person to that point to enter space,[57] and, as it proved, the only astronaut to fly Mercury, Gemini and Apollo missions.[19]

Within the first three hours of flight, the astronauts performed two actions which simulated what would be required on a lunar mission. First, they maneuvered the craft with the S-IVB still attached, as would be required for the burn that would take lunar missions to the Moon. Then, after separation from the S-IVB, Schirra turned the CSM around and approached a docking target painted on the S-IVB, simulating the docking maneuver with the lunar module on Moon-bound missions prior to extracting the combined craft.[57] After station keeping with the S-IVB for 20 minutes, Schirra let it drift away, putting 76 dặm (122 km) between the CSM and it in preparation for the following day's rendezvous attempt.[28]

The astronauts also enjoyed a hot lunch, the first hot meal prepared on an American spacecraft.[57] Schirra had brought instant coffee along over the opposition of NASA doctors, who argued it added nothing nutritionally.[58] Five hours after launch, he reported having, and enjoying, his first plastic bag full of coffee.[59]

The purpose of the rendezvous was to demonstrate the CSM's ability to match orbits with and rescue a LM after an aborted lunar landing attempt, or following liftoff from the lunar surface.[60] This was to occur on the second day; but by the end of the first, Schirra had reported he had a cold, and, despite Slayton coming on the loop to argue in favor, declined Mission Control's request that the crew power up and test the onboard television camera prior to the rendezvous, citing the cold, that the crew had not eaten, and that there was already a very full schedule.[28]

The rendezvous was complicated by the fact that the Apollo 7 spacecraft lacked a rendezvous radar, something the Moon-bound missions would have. The SPS, the engine that would be needed to send later Apollo CSMs into and out of lunar orbit, had been fired only on a test stand. Although the astronauts were confident it would work, they were concerned it might fire in an unexpected manner, necessitating an early end to the mission. The burns would be computed from the ground but the final work in maneuvering up to the S-IVB would require Eisele to use the telescope and sextant to compute the final burns, with Schirra applying the ship's reaction control system (RCS) thrusters. Eisele was startled by the violent jolt caused by activating the SPS. The thrust caused Schirra to yell, "Yabba dabba doo!" in reference to The Flintstones cartoon. Schirra eased the craft close to the S-IVB, which was tumbling out of control, successfully completing the rendezvous.[28][61]

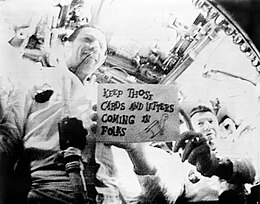

The first television broadcast took place on October 14. It began with a view of a card reading "From the Lovely Apollo Room high atop everything", recalling tag lines used by band leaders on 1930s radio broadcasts. Cunningham served as camera operator with Eisele as emcee. During the seven-minute broadcast, the crew showed off the spacecraft and gave the audience views of the southern United States. Before the close, Schirra held another sign, "Keep those cards and letters coming in folks", another old-time radio tag line that had been used recently by Dean Martin.[62] This was the first live television broadcast from an American spacecraft (Gordon Cooper had transmitted slow scan television pictures from Faith 7 in 1963, but the pictures were of poor quality and were never broadcast).[63] According to Jones, "these apparently amiable astronauts delivered to NASA a solid public relations coup."[28] Daily television broadcasts of about 10 minutes each followed, during which the crew held up more signs and educated their audience about spaceflight; after the return to Earth, they were awarded a special Emmy for the telecasts.[64]

Later on October 14, the craft's onboard radar receiver was able to lock onto a ground-based transmitter, again showing a CSM in lunar orbit could keep contact with a LM returning from the Moon's surface.[62] Throughout the remainder of the mission, the crew continued to run tests on the CSM, including of the propulsion, navigation, environmental, electrical and thermal control systems. All checked out well; according to authors Francis French and Colin Burgess, "The redesigned Apollo spacecraft was better than anyone had dared to hope."[65] Eisele found that navigation was not as easy as anticipated; he found it difficult to use Earth's horizon in sighting stars due to the fuzziness of the atmosphere, and water dumps made it difficult to discern which glistening points were stars and which ice particles.[66] By the end of the mission, the SPS engine had been fired eight times without any problems.[28]

One difficulty that was encountered was with the sleep schedule, which called for one crew member to remain awake at all times; Eisele was to remain awake while the others slept, and sleep during part of the time the others were awake. This did not work well, as it was hard for crew members to work without making a disturbance. Cunningham later remembered waking up to find Eisele dozing.[67]

Conflict and splashdown

sửaSchirra was angered by NASA managers allowing the launch to proceed despite the winds, saying "The mission pushed us to the wall in terms of risk."[41] Jones said, "This prelaunch dispute was the prelude to a tug of war over command decisions for the rest of the mission."[28] Lack of sleep and Schirra's cold probably contributed to the conflict between the astronauts and Mission Control that surfaced from time to time during the flight.[68]

The testing of the television resulted in a disagreement between the crew and Houston. Schirra stated at the time, "You've added two burns to this flight schedule, and you've added a urine water dump; and we have a new vehicle up here, and I can tell you at this point, TV will be delayed without any further discussion until after the rendezvous."[28] Schirra later wrote, "we'd resist anything that interfered with our main mission objectives. On this particular Saturday morning a TV program clearly interfered."[69] Eisele agreed in his memoirs, "We were preoccupied with preparations for that critical exercise and didn't want to divert our attention with what seemed to be trivialities at the time. ... Evidently the earth people felt differently; there was a real stink about the hotheaded, recalcitrant Apollo 7 crew who wouldn't take orders."[70] French and Burgess wrote, "When this point is considered objectively—that in a front-loaded mission the rendezvous, alignment, and engine tests should be done before television shows—it is hard to argue with him [Schirra]."[71] Although Slayton gave in to Schirra, the commander's attitude surprised flight controllers.[28]

On Day 8, after being asked to follow a new procedure passed up from the ground that caused the computer to freeze, Eisele radioed, "We didn't get the results that you were after. We didn't get a damn thing, in fact ... you bet your ass ... as far as we're concerned, somebody down there screwed up royally when he laid that one on us."[72] Schirra later stated his belief that this was the one main occasion when Eisele upset Mission Control.[72] The next day saw more conflict, with Schirra telling Mission Control after having to make repeated firings of the RCS system to keep the spacecraft stable during a test, "I wish you would find out the idiot's name who thought up this test. I want to find out, and I want to talk to him personally when I get back down."[28] Eisele joined in, "While you are at it, find out who dreamed up 'P22 horizon test'; that is a beauty also."[d][28]

A further source of tension between Mission Control and the crew was that Schirra repeatedly expressed the view that the reentry should be conducted with their helmets off. He perceived a risk that their eardrums might burst due to the sinus pressure from their colds, and they wanted to be able to pinch their noses and blow to equalize the pressure as it increased during reentry. This would have been impossible wearing the helmets. Over several days, Schirra refused advice from the ground that the helmets should be worn, stating it was his prerogative as commander to decide this, though Slayton warned him he would have to answer for it after the flight. Schirra stated in 1994, "In this case I had a cold, and I'd had enough discussion with the ground, and I didn't have much more time to talk about whether we would put the helmet on or off. I said, essentially, I'm on board, I'm commanding. They could wear all the black armbands they wanted if I was lost or if I lost my hearing. But I had the responsibility for getting through the mission."[28] No helmets were worn during the entry. Director of Flight Operations Christopher C. Kraft demanded an explanation for what he believed was Schirra's insubordination from the CAPCOM, Stafford. Kraft later said, "Schirra was exercising his commander’s right to have the last word, and that was that."[28]

Apollo 7 splashed down without incident at 11:11:48 UTC on October 22, 1968, 200 hải lý (230 mi; 370 km) SSW of Bermuda and 7 hải lý (8 mi; 13 km) north of the recovery ship USS Essex. The mission's duration was 10 days, 20 hours, 9 minutes and 3 seconds.[6][28]

Đánh giá và kết quả

sửaAfter the mission, NASA awarded Schirra, Eisele and Cunningham its Exceptional Service Medal in recognition of their success. On November 2, 1968, President Lyndon Johnson held a ceremony at the LBJ Ranch in Johnson City, Texas, to present the astronauts with the medals. He also presented NASA's highest honor, the Distinguished Service Medal, to recently retired NASA administrator James E. Webb, for his "outstanding leadership of America's space program" since the beginning of Apollo.[74] Johnson also invited the crew to the White House, and they went there in December 1968.[75]

Despite the difficulties between the crew and Mission Control, the mission successfully met its objectives to verify the Apollo command and service module's flightworthiness, allowing Apollo 8's flight to the Moon to proceed just two months later.[76] John T. McQuiston wrote in The New York Times after Eisele's death in 1987 that Apollo 7's success brought renewed confidence to NASA's space program.[64] According to Jones, "Three weeks after the Apollo 7 crew returned, NASA administrator Thomas Paine green-lighted Apollo 8 to launch in late December and orbit the Moon. Apollo 7 had delivered NASA from its trial by fire—it was the first small step down a path that would lead another crew, nine months later, to the Sea of Tranquility."[28]

General Sam Phillips, the Apollo Program Manager, said at the time, "Apollo 7 goes into my book as a perfect mission. We accomplished 101 percent of our objectives."[28] Kraft wrote, "Schirra and his crew did it all—or at least all of it that counted ... [T]hey proved to everyone's satisfaction that the SPS engine was one of the most reliable we'd ever sent into space. They operated the Command and Service Modules with true professionalism."[28] Eisele wrote, "We were insolent, high-handed, and Machiavellian at times. Call it paranoia, call it smart—it got the job done. We had a great flight."[28] Kranz stated in 1998, "we all look back now with a longer perspective. Schirra really wasn't on us as bad as it seemed at the time. ... Bottom line was, even with a grumpy commander, we got the job done as a team."[77]

None of the Apollo 7 crew members flew in space again.[78] According to Jim Lovell, "Apollo 7 was a very successful flight—they did an excellent job—but it was a very contentious flight. They all teed off the ground people quite considerably, and I think that kind of put a stop on future flights [for them]."[78] Schirra had announced, before the flight,[79] his retirement from NASA and the Navy, effective July 1, 1969.[80] The other two crew members had their spaceflight careers stunted by their involvement in Apollo 7; by some accounts, Kraft told Slayton he was unwilling to work in future with any member of the crew.[81] Cunningham heard the rumors that Kraft had said this and confronted him in early 1969; Kraft denied making the statement "but his reaction wasn't exactly outraged innocence."[82] Eisele's career may also have been affected by becoming the first active astronaut to divorce, followed by a quick remarriage, and an indifferent performance as backup CMP for Apollo 10.[83] He resigned from the Astronaut Office in 1970 though he remained with NASA at the Langley Research Center in Virginia until 1972, when he was eligible for retirement.[84][85] Cunningham was made the leader of the Astronaut Office's Skylab division. He related that he was informally offered command of the first Skylab crew, but when this instead went to Apollo 12 commander Pete Conrad, with Cunningham offered the position of backup commander, he resigned as an astronaut in 1971.[86][87]

Schirra, Eisele and Cunningham were the only crew, of all the Apollo, Skylab and Apollo–Soyuz missions, who had not been awarded the Distinguished Service Medal immediately following their missions (though Schirra had received the medal twice before, for his Mercury and Gemini missions). Therefore, NASA administrator Michael D. Griffin decided to belatedly award the medals to the crew in October 2008, "[f]or exemplary performance in meeting all the Apollo 7 mission objectives and more on the first crewed Apollo mission, paving the way for the first flight to the Moon on Apollo 8 and the first crewed lunar landing on Apollo 11." Only Cunningham was still alive at the time as Eisele had died in 1987 and Schirra in 2007.[19][76] Eisele's widow accepted his medal, and Apollo 8 crew member Bill Anders accepted Schirra's. Other Apollo astronauts, including Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Alan Bean, were present at the award ceremony. Kraft, who had been in conflict with the crew during the mission, sent a conciliatory video message of congratulations, saying: "We gave you a hard time once but you certainly survived that and have done extremely well since ... I am frankly, very proud to call you a friend."[76]

Huy hiệu sứ mệnh

sửaThe insignia for the flight shows a command and service module with its SPS engine firing, the trail from that fire encircling a globe and extending past the edges of the patch symbolizing the Earth-orbital nature of the mission. The Roman numeral VII appears in the South Pacific Ocean and the crew's names appear on a wide black arc at the bottom.[88] The patch was designed by Allen Stevens of Rockwell International.[89]

Vị trí phi thuyền

sửaIn January 1969, the Apollo 7 command module was displayed on the NASA float in the inauguration parade of President Richard M. Nixon. The Apollo 7 astronauts rode in an open car. After being transferred to the Smithsonian Institution in 1970, the spacecraft was loaned to the National Museum of Science and Technology, in Ottawa, Ontario. It was returned to the United States in 2004.[90] Currently, the Apollo 7 CM is on loan to the Frontiers of Flight Museum at Love Field in Dallas, Texas.[91]

Mô tả trên phương tiện truyền thông

sửaOn November 6, 1968, comedian Bob Hope broadcast one of his variety television specials from NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston to honor the Apollo 7 crew. Barbara Eden, star of the popular comedy series I Dream of Jeannie, which featured fictional astronauts among its regular characters, appeared with Schirra, Eisele and Cunningham.[75]

Schirra parlayed the head cold he contracted during Apollo 7 into a television advertising contract as a spokesman for Actifed, an over-the-counter version of the medicine he took in space.[93]

The Apollo 7 mission is dramatized in the 1998 miniseries From the Earth to the Moon episode "We Have Cleared the Tower", with Mark Harmon as Schirra, John Mese as Eisele, Fredric Lehne as Cunningham and Nick Searcy as Slayton.[94]

Thư viện ảnh

sửa-

Apollo 7 in flight

-

Distant view of the S-IVB stage

-

View of the Sinai Peninsula from Apollo 7

-

The Apollo 7 command module on display

Xem thêm

sửaGhi chú

sửa- ^ "Phi công Mô-đun Mặt Trăng" là chức danh chính thức được sử dụng cho vị trí phi công thứ ba trong các nhiệm vụ Block II, dù có hay không sự hiện diện của mô-đun Mặt Trăng.

- ^ Trong lĩnh vực du hành không gian, boilerplate là một mô hình tàu vũ trụ được tạo ra để kiểm tra các đặc tính của tàu vũ trụ thật.[32]

- ^ Chơi chữ họ của Wendt (đọc như "went", có nghĩa là "đã đi")

- ^ "P22" refers to Program 22 of the Apollo Guidance Computer, a means of getting a navigational fix on the spacecraft. Earlier in the day Eisele had been asked to perform "P22 horizon sightings," to which he initially replied, "What in the world is a P22 horizon sighting?"[73]

Tham khảo

sửa- ^ Orloff, Richard W. (tháng 9 năm 2004) [First published 2000]. “Table of Contents”. Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference. NASA History Series. Washington, D.C.: NASA. ISBN 978-0-16-050631-4. LCCN 00061677. NASA SP-2000-4029. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 23 tháng 8 năm 2007. Truy cập ngày 6 tháng 7 năm 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Orloff & Harland 2006, tr. 173.

- ^ “Apollo 7”. NASA. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 10 năm 2020.

- ^ “Apollo 7 (AS-205)”. National Air and Space Museum. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 4 tháng 7 năm 2017. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 10 năm 2020.

- ^ “Apollo 7 Mission Report” (PDF). Washington, D.C.: NASA. 1 tháng 12 năm 1968. tr. A-47. Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 9 tháng 10 năm 2022. Truy cập ngày 11 tháng 12 năm 2020.

- ^ a b Orloff & Harland 2006, tr. 180.

- ^ “Apollo 7”. National Air and Space Museum. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 10 năm 2020.

- ^ McDowell, Jonathan. “SATCAT”. Jonathan's Space Pages. Truy cập ngày 23 tháng 3 năm 2014.

- ^ “Apollo 7 Crew”. National Air and Space Museum. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 16 tháng 6 năm 2022. Truy cập ngày 19 tháng 4 năm 2018.

- ^ a b c Orloff & Harland 2006, tr. 171.

- ^ Press Kit, tr. 68.

- ^ French & Burgess 2007, tr. 689–691.

- ^ French & Burgess 2007, tr. 955–957.

- ^ Cunningham 2003, tr. 88–91.

- ^ Stafford 2002, tr. 552–556.

- ^ Chaikin 1995, tr. 12–18.

- ^ Scott & Leonov, tr. 193–195.

- ^ Cunningham 2003, tr. 113.

- ^ a b c Watkins, Thomas (3 tháng 5 năm 2007). “Astronaut Walter Schirra dies at 84”. Valley Morning Star. Harlingen, Texas. Associated Press. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 5 tháng 10 năm 2013. Truy cập ngày 4 tháng 10 năm 2013.

- ^ Karrens, Ed (Announcer) (1968). “1968 Year in Review: 1968 in Space”. UPI.com (Radio transcript). E. W. Scripps. United Press International. Truy cập ngày 6 tháng 7 năm 2013.

- ^ Orloff & Harland 2006, tr. 568.

- ^ Burgess & Doolan 2003, tr. 296–301.

- ^ “Oral History Transcript” (PDF) (Phỏng vấn). Johnson Space Center Oral History Project. Phóng viên Kevin M. Rusnak. Houston, Texas: NASA. 17 tháng 7 năm 2000. tr. 12-15. Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 1 tháng 5 năm 2019.

- ^ Orloff & Harland 2006, tr. 171–172.

- ^ Cunningham 2003, tr. 115–116.

- ^ Eisele 2017, tr. 38.

- ^ Eisele 2017, tr. 35–39.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Jones, Tom (tháng 10 năm 2018). “The Flight (and Fights) of Apollo 7”. Air & Space Magazine. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 10 năm 2020.

- ^ Press Kit, tr. 55–57.

- ^ Press Kit, tr. 37, 41.

- ^ Orloff & Harland 2006, tr. 110–115.

- ^ “Apollo Command Module Boilerplate”. Bảo tàng Wings. Truy cập ngày 18 tháng 7 năm 2024.

- ^ Press Kit, tr. 70–75.

- ^ Betz, Eric (18 tháng 9 năm 2018). “The First Earthlings Around the Moon Were Two Soviet Tortoises”. Discover. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 28 tháng 9 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 7 năm 2019.

- ^ Stafford 2002, tr. 616.

- ^ Pearlman, Robert Z. (3 tháng 5 năm 2010). “Guenter Wendt, 86, 'Pad Leader' for NASA's moon missions, dies”. collectSPACE. Robert Pearlman. Truy cập ngày 12 tháng 6 năm 2014.

- ^ a b Farmer & Hamblin 1970, pp. 51–54

- ^ a b c d “Day 1, part 1: Launch and ascent to Earth orbit”. Apollo 7 Flight Journal. 2 tháng 4 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 12 tháng 10 năm 2020.

- ^ “Day 1, part 3: S-IVB takeover demonstration, separation, and first phasing maneuver”. Apollo 7 Flight Journal. 2 tháng 4 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 12 tháng 10 năm 2020.

- ^ French & Burgess 2007, tr. 913.

- ^ a b Schirra 1988, tr. 200.

- ^ a b c Orloff & Harland 2006, tr. 172.

- ^ Press Kit, tr. 25–26.

- ^ “Apollo/Skylab ASTP and Shuttle Orbiter Major End Items” (PDF). NASA. tháng 3 năm 1978. tr. 5. Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 9 tháng 10 năm 2022.

- ^ a b Mission Report, tr. A-43.

- ^ Mission Report, tr. A-41.

- ^ Press Kit, tr. 29.

- ^ Shepard, Slayton, & Barbree 1994, tr. 227–228.

- ^ French & Burgess 2007, tr. 340.

- ^ a b c d Portree, David S. F. (16 tháng 9 năm 2013). “A Forgotten Rocket: The Saturn IB”. Wired. New York. Truy cập ngày 4 tháng 10 năm 2013.

- ^ Press Kit, tr. 3, 33.

- ^ Press Kit, tr. 31.

- ^ “Saturn 1B”. Space Launch Report. Ed Kyle. 6 tháng 12 năm 2012. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 10 tháng 10 năm 2010. Truy cập ngày 14 tháng 10 năm 2020.Quản lý CS1: URL hỏng (liên kết)

- ^ Press Kit, tr. 6.

- ^ Ryba, Jeanne (8 tháng 7 năm 2009). “Apollo 7”. NASA. Truy cập ngày 27 tháng 5 năm 2017.

- ^ “Day 1, part 2: CSM/S-IVB orbital operations”. Apollo 7 Flight Journal. 2 tháng 4 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 15 tháng 10 năm 2020.

- ^ a b c Wilford, John Noble (12 tháng 10 năm 1968). “3 on Apollo 7 circling Earth in 11-day test for moon trip”. The New York Times. tr. 1, 20.

- ^ Schirra 1988, tr. 192–193.

- ^ “Day 1, part 4: Remainder (preliminary)”. Apollo 7 Flight Journal. 2 tháng 4 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 17 tháng 10 năm 2020.

- ^ Press Kit, tr. 14.

- ^ Eisele 2017, tr. 63–68.

- ^ a b Wilford, John Noble (15 tháng 10 năm 1968). “Orbiting Apollo craft transmits TV show”. The New York Times. tr. 1, 44.

- ^ Steven-Boniecki 2010, pp. 55–58

- ^ a b McQuiston, John T. (3 tháng 12 năm 1987). “Donn F. Eisele, 57: One of 3 crewmen On Apollo 7 mission”. The New York Times. tr. 58.

- ^ French & Burgess 2007, tr. 1011–1012.

- ^ French & Burgess 2007, tr. 1012–1014.

- ^ French & Burgess 2007, tr. 1015–1018.

- ^ French & Burgess 2007, tr. 1021–1022.

- ^ Schirra 1988, tr. 202.

- ^ Eisele 2017, tr. 71–72.

- ^ French & Burgess 2007, tr. 1026.

- ^ a b French & Burgess 2007, tr. 1032.

- ^ “Day 9 (preliminary)”. Apollo 7 Flight Journal. 14 tháng 6 năm 2019. Truy cập ngày 27 tháng 11 năm 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Lyndon B.. "Remarks at a Ceremony Honoring the Apollo 7 Astronauts and Former NASA Administrator James E. Webb" (November 2, 1968).

- ^ a b “50 years ago, accolades for Apollo 7 astronauts”. NASA. 11 tháng 12 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 21 tháng 10 năm 2020.

- ^ a b c Pearlman, Robert Z. (20 tháng 10 năm 2008). “First Apollo flight crew last to be honored”. collectSPACE. Robert Pearlman. Truy cập ngày 12 tháng 6 năm 2014.

- ^ French & Burgess 2007, tr. 1073–1074.

- ^ a b French & Burgess 2007, tr. 1077–1078.

- ^ Benedict, Howard (22 tháng 9 năm 1968). “Oldest U.S. astronaut eyes retirement”. Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. tr. 8A.

- ^ Schirra 1988, tr. 189.

- ^ French & Burgess 2007, tr. 1074–1075.

- ^ Cunningham 2003, tr. 183.

- ^ Cunningham 2003, tr. 217–220.

- ^ French & Burgess 2007, tr. 1116–1121.

- ^ Eisele 2017, tr. 121–122.

- ^ French & Burgess 2007, tr. 1079–1082.

- ^ Cunningham 2003, tr. 291.

- ^ “Designed Insignia for Astronauts”. The Humboldt Republican. Humboldt, Iowa. 6 tháng 11 năm 1968. tr. 12 – qua Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hengeveld, Ed (20 tháng 5 năm 2008). “The man behind the Moon mission patches”. collectSPACE. Robert Pearlman. Truy cập ngày 6 tháng 7 năm 2013. "A version of this article was published concurrently in the British Interplanetary Society's Spaceflight magazine." (June 2008; pp. 220–225).

- ^ “Forty years of astronauts, moon craft in the Presidential Inaugural Parade”. collectSPACE. Robert Pearlman. 19 tháng 1 năm 2009. Truy cập ngày 21 tháng 10 năm 2020.

- ^ “Location of Apollo Command Modules”. National Air and Space Museum. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 1 tháng 6 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 27 tháng 8 năm 2019.

- ^ Paul Haney. hq.nasa.gov.

- ^ “40th Anniversary of Mercury 7: Walter Marty Schirra Jr”. NASA. Truy cập ngày 21 tháng 10 năm 2020.

- ^ “From the Earth to the Moon”. Verizon. Truy cập ngày 21 tháng 10 năm 2020.

Bibliography

sửa- Apollo 7 Mission Report (PDF). Houston, Texas: NASA. 1968. Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 9 tháng 10 năm 2022.

- Apollo 7 Press Kit (PDF). Washington, D.C.: NASA. 1968. 68-168K. Lưu trữ (PDF) bản gốc ngày 9 tháng 10 năm 2022.

- Burgess, Colin; Doolan, Kate (2003). Fallen Astronauts: Heroes Who Died Reaching for the Moon. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6212-6.

- Chaikin, Andrew (1995) [1994]. A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-024146-4.

- Cunningham, Walter (2003) [1977]. The All-American Boys . ibooks, inc. ISBN 978-1-59176-605-6.

- Eisele, Donn (2017). Apollo Pilot: The Memoir of Astronaut Donn Eisele. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6283-6.

- Farmer, Gene; Hamblin, Dora Jane; Armstrong, Neil; Collins, Michael; Aldrin, Edwin E. Jr. (1970). First on the Moon: A Voyage with Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, Edwin E. Aldrin Jr. Epilogue by Arthur C. Clarke (ấn bản 1). Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-7181-0736-9. LCCN 76103950. OCLC 71625.

- French, Francis; Burgess, Colin (2007). In the Shadow of the Moon : a Challenging Journey to Tranquility, 1965-1969 . University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1128-5.

- Orloff, Richard W.; Harland, David M. (2006). Apollo: The Definitive Sourcebook. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-30043-6.

- Schirra, Wally; Billings, Richard N. (1988). Schirra's Space. Bluejacket Books. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-792-1.

- Scott, David; Leonov, Alexei (2006). Two Sides of the Moon: Our Story of the Cold War Space Race. with Christine Toomey . St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-30866-7.

- Shepard, Alan B.; Slayton, Donald K.; Barbree, Jay; Benedict, Howard (1994). Moon Shot: The Inside Story of America's Race to the Moon. Turner Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-878685-54-4. LCCN 94003027. OCLC 29846731.

- Stafford, Thomas; Cassutt, Michael (2002). We Have Capture . Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. tr. 552–55. ISBN 978-1-58834-070-2.

- Steven-Boniecki, Dwight (2010). Live TV From the Moon. Apogee Books. ISBN 978-1-926592-16-9. OCLC 489010199.

Đọc thêm

sửa- Lattimer, Dick (1985). All We Did Was Fly to the Moon. History-alive series. 1. Foreword by James A. Michener (ấn bản 1). Alachua, FL: Whispering Eagle Press. ISBN 978-0-9611228-0-5. LCCN 85222271.

Liên kết ngoài

sửa| Wikimedia Commons có thêm hình ảnh và phương tiện truyền tải về Ctdbsclvn/nháp 1. |

- Master catalog entry tại NASA/NSSDC\

- The Apollo Spacecraft: A Chronology Lưu trữ tháng 12 9, 2017 tại Wayback Machine NASA, NASA SP-4009

- "Apollo Program Summary Report" (PDF), NASA, JSC-09423, tháng 4 năm 1975

- Phim ngắn The Flight of Apollo 7 có thể được tải miễn phí về từ Internet Archive

- The Log of Apollo 7, 1968 documentary produced by George Van Valkenburg trên YouTube